The exposure value (EV) is a number that represents a certain combination of aperture value and shutter speed (exposure time). The idea of representing these combinations as numbers belongs to a German shutter manufacturer Frederich Deckel who introduced this notation system around the middle of the 20th century (probably in the 50’s).

The exposure value scale uses the combination F1.0 (aperture) and 1.0 s (shutter speed) as origin (EV = 0). One EV unit represents the standard power of two exposure step, being equivalent to one F-stop (see “More about Aperture” post).

According to the reciprocity principle (mentioned in the post “How Much Light Is Needed Inside the Camera”), the same exposure can be achieved by more than one combination of aperture and exposure time (or shutter speed). For example, F8 and 1/60 s will produce the same exposure as F4 and 1/250 s and or F11 and 1/30 s. All the combinations will be characterized by the same exposure value.

The following table summarizes the most common EV numbers as combination of shutter speeds (rows – each row corresponds to a certain shutter speed) and aperture values (columns – each column corresponds to a certain aperture).

| T \ A | F1.0 | F1.4 | F2.0 | F2.8 | F4.0 | F5.6 | F8.0 | F11 | F16 | F22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1/4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 1/8 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 1/15 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 1/30 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 1/60 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 1/125 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 1/250 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 1/500 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 1/1000 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 1/2000 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 1/4000 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

It is not difficult to extend the table in any direction. With longer exposure times, the EV numbers become negative. Lens with apertures larger than F1.0 are extremely uncommon.

Camera manufacturers often indicate the auto exposure range in EV numbers rather than F-stops. As we saw, EV and F-stops are equivalent in the sense that one F-stop produces the same exposure difference as one EV; but the definition of EV is actually more general. It would be much better to say that a change of one EV is either produced by a one F-stop or by the equivalent change in the shutter speed (as the table above suggests).

In fully automatic exposure mode, the camera determines the optimal combination of aperture and shutter speed based on the EV calculated by the light metering system: a high EV indicates bright conditions and a low EV indicates a dark scene. In aperture priority mode the camera keeps the aperture unchanged and adjusts the exposure time (shutter speed) in order to maintain the EV constant. In shutter priority mode the camera keeps the same shutter speed but changes the aperture to maintain EV constant.

The EV scale I just described is an absolute scale. Given the automatic metering system in the camera, the absolute EV value is less important to know; in fact, most cameras will not even display the EV absolute numbers. We will use more a relative EV scale, taking as reference the EV number determined by the light metering system in the absence of any corrections. For example, if the camera determines F8 and 1/125 s as the optimal exposure for a given situation, we will consider this combination as our reference or 0 (in reality this corresponds to an absolute EV of 13). In these circumstances, a +1 EV indicates an overexposed image (for example by one F-stop) and a –1 EV indicates an underexposed image (by the same amount).

Many cameras, even some of the cheap ones, offer a manual adjustment of the exposure value determined by the camera: this adjustment is called exposure compensation. This adjustment helps in the situations where the camera cannot determine the correct EV from various reasons (for example, when taking pictures against the light); in fact, in most cases, the EV may be incorrect in a subjective way – i.e. the photographer deliberately prefers an overexposed or an underexposed image in order to achieve a certain artistic goal. In such cases, the exposure compensation gives the photographer a minimal manual control over the exposure by ±2 EV (for most cameras) to ±5 EV (for professional cameras).

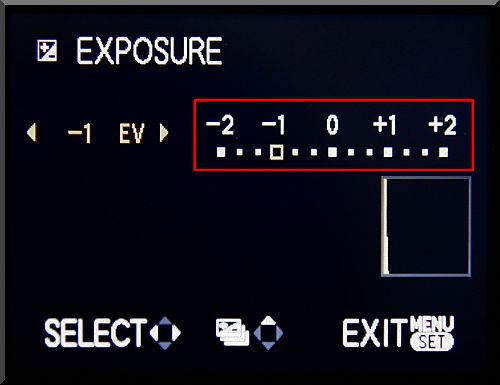

Here is a typical exposure compensation screen on a modern compact camera (the red rectangle indicates the relative EV scale with 0 for the optimal value determined by the light metering system of the camera):

Let’s assume we want to underexpose (reduce the light) by 1 EV: this means that we will select –1 EV as seen in the next screen:

As we see in this example, it is possible to adjust the exposure by smaller increments, usually 1/3 EV (most cameras) or 1/2 EV (some cameras).

Applying exposure compensation is, initially, a process of trial and error. You may want to try several times with different values and see what works best. If the scene is a landscape this isn’t a problem because you have all the time to try and review the effect right away. Sports and wild life are different: you rarely have more than one chance to take your best shot. This is where the experience of the photographer comes into play: once you are familiar with the camera metering system and the way it works in different situations you can apply the EV compensation before the shooting.

In the following posts I will continue the discussion with some examples and I will add another good technique to know – exposure bracketing – and a corresponding feature in modern cameras – the automatic exposure bracketing (AEB).

Stay tuned!