I know, I was AWOL for a while. My schedule got screwed up by lots of things: software migration and upgrades, some important deadlines at work, new toys and pet projects that required my attention. Will I be able to go back to my old habit of posting weekly? I don’t know. But I’ll try to do my best considering the amount of additional material I gathered all this time.

I’ll try to connect my previous posts about digital memory with my recent experience with Samsung Galaxy S III (SGS3) insisting on the reliability of the digital memory we use in cameras and other gadgets like smart phones, media players, etc.

My SGS3 has an internal memory of 16 GB. Some people will say that this is more than enough for a phone camera. Well, let’s estimate:

- Not all the space is used to store photos. It may be reasonable to assume that the same internal storage will be used to store documents, e-books, notes, audio files, video clips, podcasts, GPS maps or even programs (apps). I will consider the camera (photo files) storage just 8 GB.

- SGS3 camera has a resolution of 8 MPixels and uses a high quality setting by default (a compression factor around 8). According to our simplified algorithm, the image files will be around 3 MB each. However, because most of my photos are landscapes and street shots, I expect photos with a lot of details which reduce the compression and increase the file size. Indeed, based on real data, the average file size produced by SGS3 is around 4 MB.

- The estimated number of photos will be 8 GB / 4 MB = 2000. As we will see in another post, SGS3 can take HDR shots storing both the original and the HDR version – i.e. two files for one shot. Not all my photos will make a good HDR candidate, but we can apply a correction and assume 1500 photos (50% of photos will be taken in both normal and HDR modes).

- I always recommend over-provisioning (i.e. not using more than 60-70% of the storage capacity) in order to preserve the performance (especially the write speed). Our estimation drops down to about 1000 photos.

If you transfer the photos on your computer every few days, 1000 is probably enough. But many of us prefer to keep a good part of their photos in the camera in order to show them to relatives and friends. Without additional work, the “photo album” each of us keeps in their cameras and/or especially in their smart phones can reach more than 1000 photos quickly. As consequence, I’d like to add more storage (soon you’ll want more as well). In the case of compact digital cameras, storage is almost always a necessity.

Not all the smart phones allow you to add more storage – Apple’s iPhone is just an example (frustrating for some). But most others do. Especially, the Android phones, SGS3 being one of them. The preferred form factor for external digital memory used in smart phones is microSD because of its small physical size. SGS3 allows at most 64 GB of additional storage. But even 32 GB would be just fine for most of us.

In the first moment, I wasn’t willing to spend more than $25 for a microSD card. I had no intention to use my smart phone as a camera too much anyways. As consequence, I went for the best deal I could find: a Patriot LX Class 10 microSDHC 32GB (SDHC = SD High Capacity) for $19 (on sale). Patriot is not too high on my list of recommended brands – my previous experiences aren’t particularly bad but they did not impress me too much (except, maybe, for the low price). I’m still using a full size 32 GB Patriot SDHC card in my Canon SX260 HS compact camera without problems.

After using my phone for about a month and capturing few hundred photos, I was pleasantly surprised by quality of the SGS3 camera and some of its features. I began to shoot more experimenting with different settings and modes of operation. In few words, I found SGS3 camera performing very well in good light, especially for landscapes. Low light performance is a different story. But I will go back to a more in depth review of SGS3 camera in a later post.

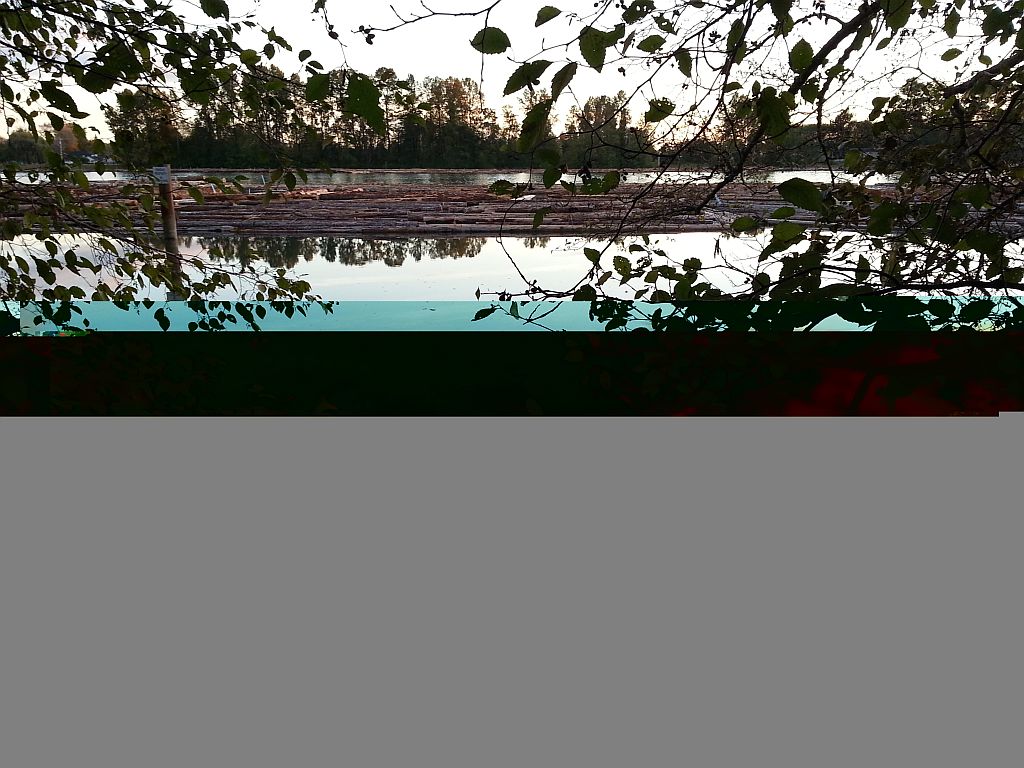

Here is another example of what this little camera can do:

One of the problems I had initially with SGS3 was the battery life, especially when using the phone with most of its modules turned on. For example, while preserving the voice calls and Internet data enabled, taking pictures with GPS tagging could drain the battery if you forget to turn the camera and the GPS off after usage. I found myself with the battery below 20% charge unexpectedly several times because I left the WiFi, GPS and camera app running. Eventually, SGS3 had a bug in the power management software that was fixed with an update from Samsung later. In the mean time, I found one way to reset the power management to a stable and economical state by restarting the phone once in a while – it takes about 15 seconds and it clears all the leftovers from the previous apps; it also restores your preferences of what modules are turned on or off by default.

One day, after a phone restart, I noticed an error message saying that the microSD card is not recognized, corrupted or formatted using an unknown file system. Hmmm… That didn’t look good. I turned off the phone immediately to prevent further damage and I removed the microSD card from the phone. Using a full size SD adapter and a flash card reader, I decided to investigate the card content with my PC, hoping to recover my photos (well… only those not saved since the last backup). Windows detected the card but asked me to format it before usage – a clear indication that the card format (normally FAT32) was not recognized; no matter what I tried, I could not make Windows access my files.

First lesson learned: never rely on the memory card in your camera (or phone) to store your content (photos, videos, audio files, etc.) for a long time.

As a computer engineer, I was intrigued by the problem and decided to go deeper: I wanted to know what went wrong. Before anything else, I copied the card content on the hard drive as plain unformatted data: a huge 32 GB binary file that, eventually, contained my photos. The best tool for such operations is probably WinImage. After few hours of investigation, I came to the conclusion that the file system structure was altered in an unrecoverable way. Normally, I would have stopped here and reformat the card. But I wanted to try some recovery tools before anything else.

Second lesson: as soon as you notice data corruption on your flash card, turn everything off, remove the card from the device and, if possible, copy its contents as a binary image using a disk imaging utility like WinImage for further investigation.

The ability to recover files relies on the fact that, while the file system structure (here FAT32) has been altered, the data itself is still present somewhere on the card but the computer (or the phone/camera) doesn’t know where to find it. The recovery programs usually scan the entire card looking for known patterns specific to different file types to begin the recovery process. This may sound simple, but, believe me, it is not!

Currently, there are a lot of file recovery programs: some paid, some free. I began with the free ones. Searching on Internet for such programs will produce tens of such programs; which one to trust it will do a good job? Based on some positive reviews, I decided to try Recuva, Pandora Recovery, Zar and PC Inspector. The results weren’t very good in my case (about 10…20% recovery rate), despite the reviews I just mentioned. Maybe my card was corrupted beyond what a free recovery tool can do. I managed to get some of my photos but not in a very good state (see below).

In the last moment, I remembered that, together with one of my Lexar cards bought two years ago, I’ve also got a recovery utility – Image Rescue – a $35 bonus that I never used. I decided to try and, to my surprise, after few hours of work, the program recovered most of my files including video clips and some documents. Even without the card bonus, paying $35 isn’t probably too much for your peace of mind. By the way, when it comes to flash memory cards, Lexar is a good brand that deserves your consideration.

Third lesson: use a good and tested file recovery tool – the free ones may work well in some cases but the ones provided by the card manufacturers or companies specialized in data recovery work best. Beside the quality and reliability of their products, reputable card manufacturers may offer file recovery and/or backup software, usually included in the price of the cards.

I ended up buying a SanDisk Ultra 32 GB microSD card to replace the old one in my phone (see below). This card was especially designed for smart phones to ensure an optimal combination of performance and reliability and it comes with a full size SD adapter if you want to use it in other devices like a digital compact camera. And the price tag ($30) wasn’t too far from my initial target ($25).

The following questions remain:

- Was the quality of the Patriot card low?

- Did I get one from a faulty batch?

- Was the SGS3 software faulty?

- Was it just a SGS3 hardware glitch?

Probably I will never get the right answer but I didn’t want to take chances. Moreover, I’m backing up my data even more often to minimize any possible loss.

Forth lesson: always backup your files on a computer – more about backing up your photos in a future post.

I’m still using the Patriot card reformatted and loaded with audio files in a media player without problems. It is true that the usage profile is different, the card being used much less for writing (where most of the corruption problems appear).

A final note: the file system used in most of these cards is FAT32, a file system designed originally for hard drives. Flash cards have different failure mechanisms that FAT32 do not address. As consequence, hardware or software glitches can produce data corruption with higher probability than hard drives. There are proposals of new file systems that will provide immunity to corruption problems – the only thing making the transition difficult is the popularity of the FAT32 format and the huge number of devices already using it. Other solutions to mitigate data corruption rely on the memory controllers in the flash card to implement data protection while preserving a file system like FAT32; unfortunately, the high complexity of the protection algorithms produce successful results only in part. This is where the card manufacturer reputation is built – solid and well established manufacturers spend more in R&D, are usually better in doing it right in production, and have a better quality control, since the better reliability.

As consequence, spend your money wisely – few good flash cards, even somewhat more expensive, can last a very long time without data loss.

In summary:

- Never rely on the memory card in your camera (or phone) to store your content (photos, videos, audio files, etc.) for a long time.

- As soon as you notice data corruption on your flash card, turn everything off, remove the card from the device and, if possible, copy its contents as a binary image for backup and investigation.

- Use a good and verified file recovery tool to salvage your files; the better the tool, the more chances you will have to recover almost (if not) everything.

- Don’t wait for disasters: always backup your files on a computer, eventually on two different types of media (e.g. external hard drive and optical disc).